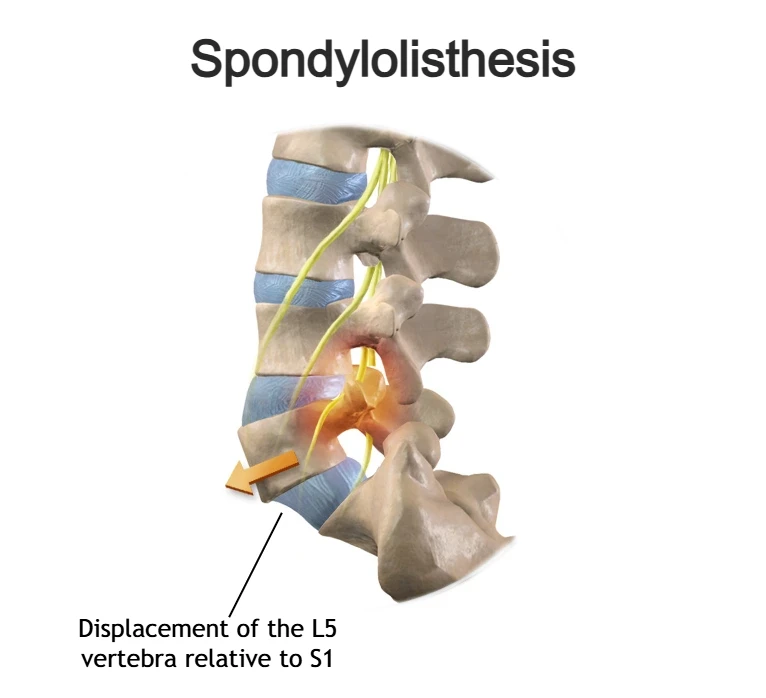

Spondylolisthesis is a condition characterized by the forward displacement of one vertebra in relation to the adjacent vertebra. It can occur in any part of the spine, but it most commonly affects the lumbar (lower) spine. Spondylolisthesis may develop for various reasons, including congenital (present at birth) spinal abnormalities, changes that occur over time such as degenerative processes, injuries or fractures, or in some cases without a clearly identifiable cause (idiopathic spondylolisthesis).

While some patients experience no symptoms at all, others may develop low back pain. In more advanced cases, neurological symptoms can occur, such as weakness, numbness, tingling, or pain radiating into the legs. It is important to emphasize that the majority of patients do not require surgical treatment and can be successfully managed with conservative, non-surgical approaches.

In this article, we will explain what spondylolisthesis is, how its severity is assessed, how the diagnosis is made, and which treatment options are available.

What Is Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolisthesis definition?

Spondylolisthesis is a condition in which one vertebra shifts or “slides” in relation to the adjacent vertebra. The term comes from Greek and literally means “slipping of a vertebra,” which accurately describes the nature of this condition.

The vertebral displacement can occur forward (anterolisthesis), sideways (laterolisthesis), or backward (retrolisthesis) relative to the neighboring vertebra. Spondylolisthesis may develop at any level of the spine, but it most commonly affects the lower (lumbar) spine—particularly the junction between the L5 and S1 vertebrae.

This condition can arise from various factors, including congenital abnormalities in spinal structure, degenerative changes of the spine, or traumatic injuries. Symptoms can vary widely, ranging from no noticeable discomfort to lower back pain, stiffness, and neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, or weakness.

To better understand spondylolisthesis and its different clinical presentations, it is important to distinguish between several related terms that describe the direction and nature of vertebral displacement.

Ventrolisthesis, Anterolisthesis, Retrolisthesis, and Pseudospondylolisthesis

- Ventrolisthesis – describes anterior displacement of a vertebra relative to the vertebra below. The term is often used interchangeably with anterolisthesis in clinical practice.

- Anterolisthesis – refers to forward slipping of a vertebra and is the most common form of spondylolisthesis, particularly in the lumbar spine.

- Retrolisthesis – indicates backward displacement of a vertebra relative to the adjacent vertebra and is less common than anterolisthesis.

- Pseudospondylolisthesis – a term used to describe apparent vertebral displacement caused by degenerative changes, such as disc height loss and facet joint degeneration, without a true defect or instability of the vertebra.

Why Does Spondylolisthesis Develop and What Are the Main Types?

Spondylolisthesis can develop for a variety of reasons, but it most commonly results from a combination of mechanical stress and the gradual degenerative wear of the spine. In some individuals, congenital anatomical features that reduce spinal stability may further increase the risk of developing spondylolisthesis. Over time, these factors can lead to progressive loss of spinal stability and vertebral slippage, with the condition potentially worsening as time goes on.

Spondylolisthesis is most often associated with age-related degenerative changes of the spine (spondylosis) and typically occurs in people over the age of 60—a condition known as degenerative spondylolisthesis. Another form, more common in younger individuals, is isthmic spondylolisthesis, which is frequently seen in children, adolescents, and young adults.

Below, we outline the most common types of spondylolisthesis and explain how and why they develop:

Types and classifications of spondylolisthesis:

1. Dysplastic (Congenital) Spondylolisthesis

Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is a form of spondylolisthesis that develops due to congenital (present at birth) structural abnormalities of the lower spine, most commonly at the junction between the lumbar spine and the sacrum (L5–S1). These anatomical variations—such as underdeveloped facet joints, a dysplastic sacrum, or mild forms of spina bifida—reduce the overall stability of the spine.

As a result of altered biomechanics and increased shear forces at the lumbosacral junction, the affected vertebra is more prone to earlier and more pronounced forward slippage. This can lead to higher-grade vertebral displacement and, in some cases, visible spinal deformity.

2. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Isthmic spondylolisthesis develops as a result of a defect or fracture in a specific part of the vertebra known as the pars interarticularis (pars fracture), leading to a loss of stability of the posterior elements of the spine. This defect—referred to as spondylolysis—allows the vertebral body to gradually slip forward.

This form of spondylolisthesis is most commonly associated with repetitive mechanical stress, particularly in adolescents and young adults who participate in sports involving frequent spinal extension and rotation. Activities such as gymnastics, football, and wrestling place repeated stress on the lower back. Individuals with a congenitally thinner pars interarticularis may be at higher risk of developing this condition.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis is further classified into several subtypes:

- Type IIA — stress fractures of the pars interarticularis caused by repetitive loading

- Type IIB — elongation of the pars interarticularis due to repeated microtrauma and incomplete healing

- Type IIC — acute traumatic fracture of the pars interarticularis resulting from a direct injury

Pars Fracture and Its Role in Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

A pars fracture refers to a stress or acute fracture of the pars interarticularis, a key structural component of the vertebra. This type of fracture is the underlying cause of spondylolysis and plays a central role in the development of isthmic spondylolisthesis. Repeated mechanical loading, especially during spinal extension and rotation, can lead to microfractures that weaken the pars interarticularis and allow forward vertebral slippage over time.

3. Degenerative Spondylolisthesis – The Most Common Type

Degenerative spondylolisthesis develops as a result of the gradual degeneration of the structures that stabilize the spine, primarily the intervertebral discs and the small facet joints between vertebrae. Over time, this leads to reduced disc height, facet joint osteoarthritis, and loss of support in the posterior part of the spine, which increases stress on the anterior portion and encourages vertebral slippage.

This type most commonly occurs at the L4–L5 level and is typical in older adults—especially women—due to age-related changes in bone density, ligament elasticity, and spinal biomechanics. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is the most frequent form of spondylolisthesis in the elderly population.

4. Traumatic Spondylolisthesis

Traumatic spondylolisthesis occurs as a result of an acute spinal injury, most often due to fractures or dislocations of the posterior elements of the vertebra (excluding the pars interarticularis fracture).

Unlike other forms, this type is not caused by gradual wear and tear but rather by the direct impact of a strong force.

It is commonly associated with injuries such as car accidents, falls from height, or severe sports trauma. Due to the sudden loss of spinal stability, traumatic spondylolisthesis may be accompanied by significant pain, spinal deformity, and, in severe cases, neurological symptoms, which makes prompt medical assessment and treatment essential.

5. Pathologic Spondylolisthesis

Pathologic spondylolisthesis develops as a result of diseases that weaken the spinal structure, such as tumors, infections, or metabolic bone disorders. These conditions compromise the strength of the vertebrae and surrounding structures, making the spine more susceptible to vertebral slippage and loss of stability.

6. Iatrogenic (Postoperative) Spondylolisthesis

Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis can develop following spinal surgery, particularly when a significant amount of bone tissue is removed during decompression. Extensive laminectomy can weaken the pars interarticularis and posterior stabilizing structures, increasing the risk of iatrogenic spondylolysis and subsequent vertebral slippage.

Symptoms of Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis does not always cause symptoms, especially in mild cases. Many people may have this condition for years without knowing it, as they experience no pain or functional limitations.

When symptoms do occur, the most common complaint is low back pain (in lumbar spondylolisthesis) or neck pain (in cervical spondylolisthesis). This pain can be difficult to distinguish from discomfort caused by age-related degenerative changes of the spine (spondylosis) and usually worsens with bending, physical activity, or prolonged standing. Some patients experience sharp pain with certain movements, such as bending forward or twisting the spine backward, due to mechanical instability in the affected segment.

A slipped vertebra can also narrow the space through which spinal nerves pass. If the displaced vertebra compresses nerve roots, neurological symptoms may develop, including radiating leg pain, numbness, weakness, or loss of sensation.

The effect of nerve compression can be further aggravated by other degenerative changes in the spine, such as bone spurs (osteophytes), thickened ligaments, facet joint osteoarthritis, and intervertebral disc protrusion.

Common neurological symptoms include:

- Sharp or shooting pain radiating into the leg (radicular pain, sciatica)

- Numbness, tingling, or loss of sensation in the buttocks and legs

- Leg weakness and a sense of instability while walking

- Difficulty walking or standing for prolonged periods

Some patients notice that symptoms improve in certain positions, such as lying down, which reduces pressure on the nerves.

In rare and severe cases, especially with significant spinal canal narrowing, there may also be bladder or bowel control problems, which require urgent medical evaluation.

How Is Spondylolisthesis Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of spondylolisthesis begins with a patient interview and physical examination. The doctor evaluates posture, looks for a “step-off” deformity (a palpable shift between vertebrae), checks for an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, and assesses tenderness and range of motion, especially pain during spinal extension.

An important part of the exam is a neurological assessment, which includes testing muscle strength, sensation, and reflexes to determine whether nerve structures are being compressed. Neurological deficits may indicate involvement of spinal nerve roots.

Laboratory tests are usually not necessary, unless there are signs of infection, inflammatory disease, or metabolic disorders.

Imaging Tests for Spondylolisthesis

The primary imaging method for diagnosing and assessing the severity of spondylolisthesis is X-ray. Depending on the case, other imaging modalities such as MRI and CT scans may also be used:

- X-rays (front, side, and functional views) are the standard method to evaluate vertebral alignment, spinal stability, and the degree of spondylolisthesis according to the Meyerding classification.

- CT (Computed Tomography) is the best technique for detecting pars fractures and bony changes, making it especially useful for preoperative planning.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is used to assess nerve structures, intervertebral discs, and soft tissues, and to detect nerve compression.

It is important to note that the presence of spondylolisthesis on imaging does not necessarily mean it is the cause of pain. Many people have radiologically visible vertebral slippage but experience no symptoms. Therefore, imaging tests are not always required nor decisive for treatment decisions, especially if there are no signs of significant neurological compromise.

Imaging becomes necessary in emergency situations or when there is suspicion of other causes of symptoms—such as a vertebral fracture, infection, or tumor.

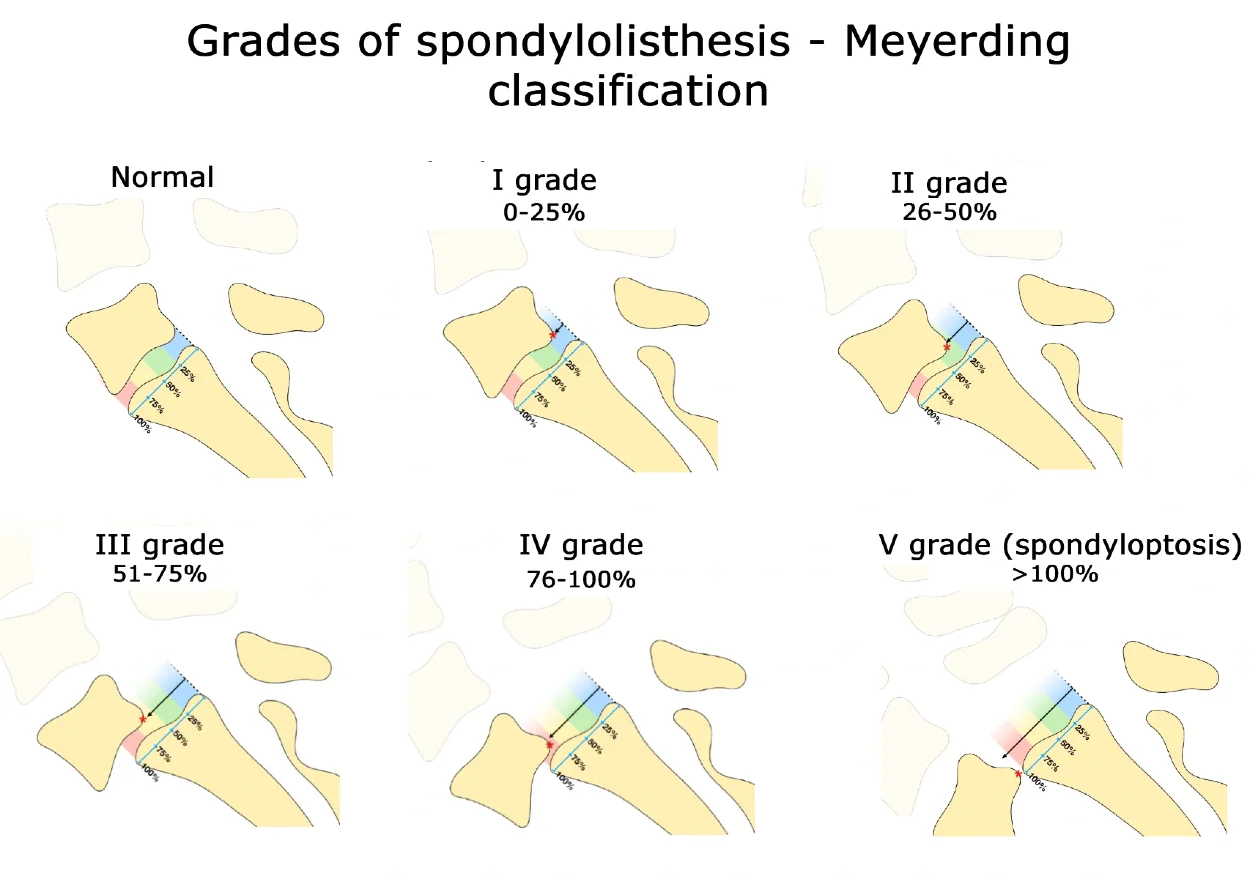

Spondylolisthesis Grades: Meyerding Classification

The severity of spondylolisthesis is assessed using spondylolisthesis grades, which are determined based on radiological imaging. These grades measure how much one vertebra has slipped forward relative to the vertebra below. The most widely used system for evaluating spondylolisthesis grades is the Meyerding classification, developed by a surgeon at the Mayo Clinic.

Meyerding’s classification is based on the percentage of vertebral slippage and divides spondylolisthesis into the following grades:

- Grade I — 1% to 25% slippage

- Grade II — 26% to 50% slippage

- Grade III — 51% to 75% slippage

- Grade IV — 76% to 100% slippage

- Grade V (Spondyloptosis) — more than 100% slippage, where the vertebra has completely slipped in front of the one below

For practical purposes, vertebral slippage is often grouped into two categories:

- Low-grade spondylolisthesis — Grades I and II

- High-grade spondylolisthesis — Grades III, IV, and V

A higher grade of slippage does not necessarily mean more severe symptoms, but it is associated with an increased risk of pain, spinal instability, and neurological problems.

Treatment of Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis may or may not cause symptoms. In some people, it can go completely unnoticed. If spondylolisthesis is discovered incidentally and does not cause pain or other problems, treatment is not necessary.

If symptoms are present—such as lower back pain, numbness, or tingling in the legs—various treatment options are available to relieve discomfort and improve daily functioning. In most cases, spondylolisthesis is managed with conservative, non-surgical methods, while surgery is considered only in certain situations.

For those with spondylolisthesis, it is recommended to stay as active as possible, within the limits of symptoms. At the same time, short periods of rest can help reduce discomfort, especially during flare-ups of pain. The goal of treatment is to find a balance between activity and rest, reducing pain while maintaining mobility and function.

Below, we will focus on conservative treatment measures—what you can do on your own, the role of exercises, how physical therapy can help manage symptoms, when medications may be needed, and how these strategies can improve quality of life.

How to help yourself if you have spondylolisthesis

There are several everyday measures that can help reduce pain and make it easier to cope with the symptoms of spondylolisthesis. In most cases, these simple strategies form the foundation of conservative management.

Stay active

It is generally recommended to remain as active as possible and, if symptoms allow, to maintain your usual level of movement. Prolonged avoidance of activity can lead to muscle weakness and loss of bone strength, which may worsen symptoms over time. Clinicians often encourage continuing daily activities, especially if pain can be kept under control. Regular movement can also have a positive effect on mood and overall well-being.

Choose appropriate activities

Some activities are better tolerated than others. Walking, particularly on flat ground or a slight incline, is often well tolerated because the trunk naturally leans slightly forward, reducing pressure on the lower spine. Cycling can also be a good option. Backstroke swimming and water-based exercises reduce spinal loading and are often easier to tolerate.

Pay attention to posture

A slight forward-leaning posture and proper pelvic alignment can reduce pressure on neural structures. A physiotherapist can help teach optimal posture and movement patterns, especially if the lower back is weak or stiff. It is also helpful to change positions frequently throughout the day rather than remaining seated or standing in the same position for long periods.

Exercise and spondylolisthesis — YES or NO?

In general, exercise is not harmful for most people with low back pain, and this also applies to most individuals with spondylolisthesis. Many patients worry that movement might further “damage” the spine, especially when pain is present. This fear is understandable—acute pain is often perceived as a warning sign—but in most cases there is no serious or dangerous structural damage to the spine.

Despite radiologically confirmed spondylolisthesis, it is very unlikely that exercise will cause the vertebra to slip further or lead to compression of nerves or other structures. Although this scenario may seem logical, in practice it is extremely rare.

Research shows that people who remain active and have confidence in their ability to move tend to cope better with symptoms and are less likely to experience them as a major limitation in daily life. In contrast, excessive focus on pain is often associated with more intense and longer-lasting symptoms.

How to find the right balance between exercise and rest

Finding the right balance between activity and rest is not always easy. Some people, out of fear of pain, completely stop many activities. Over time, this can lead to weakening of muscles, bones, and the cardiovascular system, ultimately worsening pain. In addition, giving up activities you enjoy and that are important in daily life can have a negative psychological impact.

On the other hand, some individuals continue with all activities as before, ignoring their symptoms. This often results in overloading the spine and aggravation of symptoms.

For this reason, it is helpful to find a healthy middle ground and gradually improve physical conditioning through small but thoughtful adjustments:

- breaking larger tasks and activities into smaller, more manageable parts

- setting priorities and focusing on what truly matters

- adapting personal goals to current abilities

- planning ahead and preparing for possible pain, rather than reacting only when it occurs

This approach helps maintain control over symptoms while preserving an active and good-quality everyday life.

Physical therapy for spondylolisthesis

Physical therapy can help relieve symptoms, at least temporarily, especially during periods of increased pain. It includes a range of interventions aimed at reducing pain, improving mobility, and enhancing spinal stability.

In clinical practice, pain-relieving modalities such as laser therapy, magnet therapy, ultrasound, and electrotherapy are commonly used to reduce pain and muscle tension. Manual therapy may also be beneficial; during these sessions, the therapist uses specific techniques to mobilize joints and soft tissues in order to improve mobility of the spine, pelvis, and hips, and to reduce muscle tightness that affects posture.

An essential component of physical therapy is strengthening and postural correction exercises, particularly exercises targeting the core muscles and lower limbs, which help stabilize the spine. These exercises also have a positive effect on overall fitness and mobility.

It is crucial to continue exercising even after formal physical therapy has ended and to make these exercises part of a regular daily routine.

It is important to note that the effects of therapy can vary from person to person. Some individuals respond well to passive treatments such as heat therapy or massage, which they find relaxing and soothing, while others benefit more from active, exercise-based approaches.

Wearing a brace (orthosis) — is it a good idea?

In some cases, a physician may recommend a spinal brace (orthosis) with the aim of stabilizing the spine and pelvis and reducing pain.

Personally, I am not a strong advocate of routine brace use for low back pain.

If a brace is used, it should not be worn continuously or for prolonged periods, as this may lead to weakening of the core muscles that normally stabilize the trunk and may actually worsen symptoms over time. Spinal orthoses should always be prescribed by a physician and used strictly according to professional guidance.

Pain medications

Medications can help relieve pain and make movement easier, which in turn helps you stay active. The most commonly recommended drugs are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as diclofenac or ibuprofen. They should be taken only when necessary and at the lowest effective dose.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is generally not effective for pain caused by spondylolisthesis and is therefore not usually the first treatment option.

Opioids, such as tramadol, are not more effective than NSAIDs for this type of pain and may carry a risk of dependence and various side effects, so their use is generally avoided.

In certain situations, physicians may prescribe antiepileptic or antidepressant medications to help with neuropathic pain when nerve roots are affected, causing tingling or burning sensations in the legs. However, their effectiveness for spondylolisthesis-related pain is limited and not well established.

Injections

Another option for relieving pain in spondylolisthesis is spinal injections of medications, such as steroids and/or anesthetics, directly into the spine near the narrowed part of the spinal canal to reduce nerve irritation. The most commonly used procedure is the epidural injection, in which the physician uses CT or X-ray imaging to precisely locate the injection site.

It is important to understand that these injections usually provide temporary relief, often lasting only a few weeks. They can also have side effects, including bleeding, infection, or nerve injury. Therefore, they are administered only under clear medical indication and professional supervision.

Surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis

For patients with spondylolisthesis accompanied by spinal canal narrowing (stenosis) and symptoms that persist for several months despite conservative treatment, spinal surgery may be considered. It is important to note that complete pain relief is not guaranteed, but surgery can stabilize the spine and alleviate neurological symptoms.

In degenerative spondylolisthesis, the most common surgical approach involves decompression of the affected nerve structures, often combined with spinal fusion. Fusion helps stabilize the spine, prevent further vertebral slippage, and maintain proper spinal biomechanics. There are several fusion techniques—posterior, transforaminal, or anterior—depending on the anatomy, degree of slippage, and presence of instability. Minimally invasive variants of these procedures are sometimes used to reduce surgical trauma and speed up recovery.

In more severe cases, known as high-grade spondylolisthesis, surgeons may consider vertebral reduction to restore proper sagittal alignment of the spine and reduce the risk of further degenerative changes. However, this procedure requires high surgical expertise and carries an increased risk of neurological complications. When the spine is in an acceptable alignment, in situ fusion can be performed, stabilizing the vertebrae without additional reduction, thereby reducing surgical risk.

After surgery, structured and guided rehabilitation is an essential part of recovery to restore mobility, strength, and function.

Living with spondylolisthesis

It is important to understand that there is no cure for spondylolisthesis. Back and leg pain is usually chronic, although some days may be better than others. Despite this, most patients are able to lead normal lives. Therefore, it is helpful to accept the condition and be cautious of unrealistic promises of complete recovery.

The prognosis for low-grade spondylolisthesis is generally favorable—many patients remain symptom-free or experience only minimal progression over time. In adults with mild vertebral slippage, significant progression is rare, although degenerative changes in the spine, such as disc degeneration and facet joint arthrosis, can worsen the clinical picture.

On the other hand, high-grade spondylolisthesis carries a more guarded prognosis due to a higher risk of progression and complications. These cases often involve pronounced mechanical instability, disrupted sagittal spinal alignment, and neurological symptoms.

However, there is much that can be done individually. It is useful to educate yourself about the condition and observe which activities worsen symptoms and which alleviate them. Based on this, you can adapt your daily routines—plan adequate rest, remain flexible with activities, and make decisions about what to do depending on how you feel.

Ultimately, mindful management of symptoms and adjusting everyday life often holds the key to maintaining a good quality of life with spondylolisthesis, even without completely eliminating pain.

Margetis K, Gillis CC. Spondylolisthesis . [Updated 2025 Mar 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Overview: Spondylolisthesis . 2025 Sep 12.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Spondylolisthesis: Learn More – Non-surgical treatment for spondylolisthesis . 2025 Sep 12.

Koslosky E, Gendelberg D. Classification in Brief: The Meyerding Classification System of Spondylolisthesis . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020 May;478(5):1125–1130. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001153. PMID: 32282463; PMCID: PMC7170696.