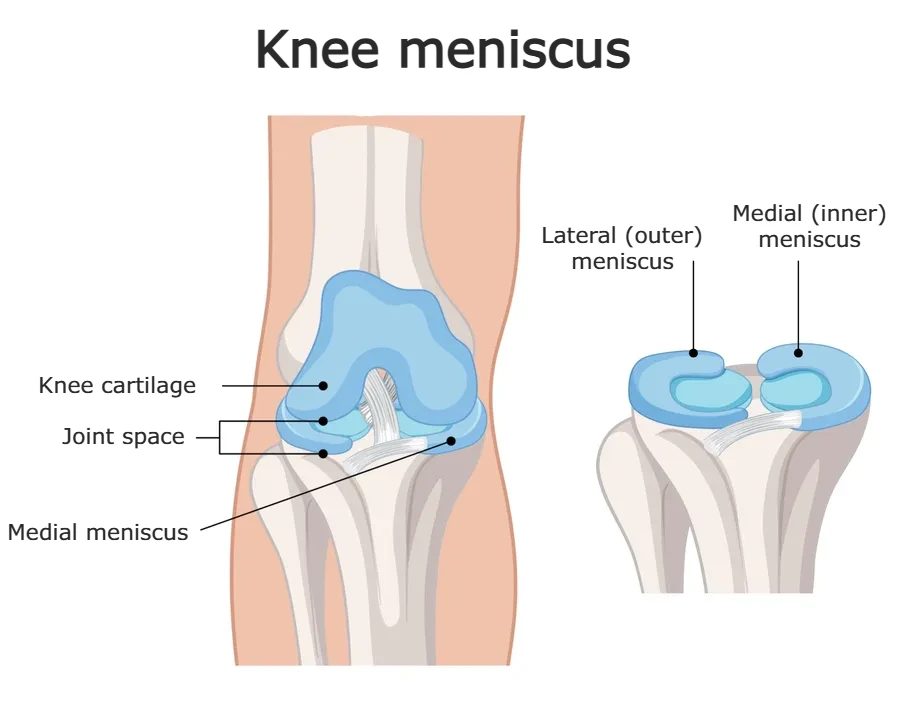

The meniscus is a crescent-shaped piece of cartilage located between the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia) in the knee joint. Each knee has two menisci — the medial meniscus on the inside and the lateral meniscus on the outside. These structures play a crucial role in absorbing shock, distributing body weight, and reducing friction within the joint, helping to protect the cartilage and allow for smooth, stable movement.

Meniscal tears are among the most common knee injuries and a frequent cause of knee pain. A tear can occur suddenly due to trauma — such as twisting the knee during sports or a fall — or gradually over time as a result of degenerative changes associated with aging.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at how and why meniscal injuries happen, what the typical symptoms are, and how the condition is diagnosed and treated. We’ll also discuss the recovery process, including how long it takes to heal — especially after meniscus surgery — and what to expect during recovery.

Meniscus Anatomy and Function

The knee is a hinge joint that connects the femur (thigh bone) to the bones of the lower leg — the tibia (shinbone) and fibula (calf bone). Between the femur and tibia, there are two crescent-shaped cartilage structures known as the menisci (singular: meniscus), which act as cushions within the joint.

Each knee has two menisci:

- The medial meniscus on the inner side of the knee

- The lateral meniscus on the outer side

Both are essential for maintaining knee stability, load distribution, and smooth joint movement.

Structurally, the meniscus is made up mostly of water (about 72%) and an extracellular matrix composed primarily of type I collagen fibers, which give it strength and flexibility. In shape, each meniscus resembles a curved “C” or crescent.

Blood Supply and Healing Potential

The meniscus has limited blood supply, which affects its ability to heal. The outer third, known as the “red zone,” is better supplied with blood and has a higher capacity for healing. In contrast, the inner two-thirds, called the “white zone,” receive little to no direct blood flow and rely on diffusion from synovial fluid for nourishment. This difference is critical — tears in the red zone may heal on their own or respond better to surgical repair, while tears in the white zone often have poor healing potential.

Function of the Meniscus

The menisci cover roughly 70% of the surface area of the tibial plateau (the top of the shinbone). Their primary roles include:

- Shock absorption during weight-bearing activities

- Even distribution of body weight across the joint

- Reduction of friction between the femur and tibia

- Enhancement of joint stability, especially during movement and rotation

These functions help protect the articular cartilage and allow the knee to move smoothly and efficiently. Damage to the meniscus can compromise joint mechanics and increase the risk of long-term issues like osteoarthritis.

How and Why Do Meniscal Tears Happen?

Meniscal tears occur either as a result of injury — typically in younger, active individuals — or due to degenerative changes that develop over time, particularly in middle-aged and older adults. Based on the cause, we generally classify meniscal tears into two main categories:

- Acute (traumatic) meniscal tears

- Degenerative meniscal tears

Acute Meniscal Tears

Young people, especially athletes, often experience these injuries during sports that involve quick direction changes, pivoting, or high-impact movements — such as football, basketball, skiing, or handball.

Acute tears are usually caused by sudden and forceful knee movements, including:

- Quick changes in direction while running

- Twisting of the knee while the foot is planted

- Deep squatting under load

- Direct blows to the knee

A typical injury scenario might involve a slightly bent knee with the foot firmly planted on the ground. When the upper body rotates suddenly, a combination of compression and torsion occurs in the knee joint, placing intense stress on the meniscus. Sports like football, where these movements are frequent, pose a particularly high risk — both with and without physical contact.

In contact sports, a classic mechanism involves a direct hit to the outer side of the knee while it is partially bent and the foot is fixed. These injuries are often associated with damage to other structures, particularly the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or medial collateral ligament (MCL).

Meniscal tears may also occur during non-sport-related trauma, such as car accidents or falls from height onto the legs.

Degenerative Meniscal Tears

As we age, the menisci naturally undergo changes — a process known as degeneration. Over time, the meniscus becomes thinner, less elastic, and more prone to tearing, even under relatively low stress.

Unlike acute tears, degenerative tears often don’t require a major injury. Something as simple as twisting the knee while standing up from a chair or turning awkwardly during daily activities may be enough to tear a weakened meniscus.

Degenerative tears are most commonly seen in individuals over the age of 40, and are frequently associated with knee osteoarthritis (a degenerative joint condition). People with physically demanding jobs that involve frequent kneeling, squatting, climbing ladders, or lifting heavy objects are at greater risk for these types of tears.

| Feature | Acute Meniscal Tear | Degenerative Meniscal Tear |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Age Group | Younger, active individuals | Adults over 40 |

| Cause | Sudden injury or trauma (e.g. twisting, impact) | Gradual wear and tear over time |

| Activities Involved | Sports like football, basketball, skiing | Daily activities or occupational stress |

| Associated Injuries | Often with ACL or MCL injuries | Often linked with osteoarthritis |

| Onset | Sudden and clearly remembered event | Gradual onset, may go unnoticed at first |

Meniscus Tear Symptoms

The symptoms of a meniscus tear can vary depending on how the injury occurred and whether other knee structures (like ligaments) are also damaged. In acute injuries, symptoms usually appear immediately or within the first 1–3 days after a traumatic event. In contrast, degenerative tears tend to develop gradually over time, without a clear moment of injury.

A common scenario in sports involves a sudden “popping” sensation in the knee, followed by swelling. This may indicate an ACL injury, often accompanied by a medial meniscus tear. On the other hand, if the knee swells slowly within 24 hours — without a clear traumatic event — it may suggest an isolated meniscus tear. In both cases, the most common and persistent symptom is knee pain.

Most Common Symptoms of a Meniscus Tear

- Knee pain, especially when walking, climbing stairs, or walking on uneven surfaces. Pain is usually felt on the inside of the knee in medial tears and on the outer side in lateral tears.

- Swelling and stiffness, especially after physical activity or prolonged standing.

- Catching, locking, or “clicking” sensation in the knee. Some patients feel like the knee “gets stuck” when trying to move it. In more severe cases, a torn piece of meniscus can become trapped in the joint, causing a true knee lock — where the leg cannot fully extend.

- Instability or a sensation of the knee “giving way”, especially during walking or standing.

- Limited range of motion, including difficulty fully bending or straightening the knee.

Does Every Meniscus Tear Cause Pain?

In short — no.

Not every meniscus tear is painful, and not all of them cause symptoms.

Meniscal tears are often found incidentally during an MRI of the knee — especially in older adults. In fact, up to 60% of people with a visible meniscus tear on MRI report no knee pain or symptoms at all.

This means that the presence of a meniscus tear on imaging does not always explain why someone is experiencing knee pain. In many cases, especially in people over the age of 50, meniscus tears are simply a part of the natural aging process, much like wrinkles or graying hair.

Some meniscus tears cause sharp pain, swelling, or mechanical symptoms like locking. Others cause no symptoms at all and often don’t require treatment, especially when doctors discover them incidentally and they aren’t causing any problems.

Meniscus Tear Diagnosis (Testing for Meniscus Tear)

If you’re experiencing knee pain or symptoms suggestive of a meniscus injury, the first step is a clinical evaluation by a physician — typically a physical medicine specialist or orthopedic surgeon. Diagnosis begins with a conversation about your symptoms, activity level, and (if applicable) the mechanism of injury.

The doctor will then perform a detailed physical examination of your knee, checking for:

- Range of motion

- Swelling or joint effusion

- Tenderness over the joint line

- Signs of mechanical block (inability to fully straighten the knee)

- Instability or abnormal movement

Interestingly, the intensity of symptoms doesn’t always reflect the severity or location of the tear. Some people with small tears may have severe symptoms, while others with more extensive damage may feel only mild discomfort.

Meniscus Tear Test

During your exam, your doctor may perform a series of special maneuvers known as meniscal tests, designed to stress the joint and reproduce symptoms if a tear is present. These include:

- McMurray Test

- Thessaly Test

- Apley Compression Test

While these tests can help point toward a meniscus injury, none of them are 100% conclusive. They are most useful when combined with your history and symptom pattern. A positive test doesn’t confirm a tear — and a negative one doesn’t rule it out completely.

Meniscus Tears MRI: The Gold Standard

Standard X-rays are not useful for detecting meniscus tears, since cartilage is not visible on radiographs. However, X-rays may still be ordered to check for other causes of knee pain, such as osteoarthritis, which is common in older adults.

When a meniscus tear is suspected, the most accurate imaging method is MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). MRI can visualize soft tissues like cartilage, ligaments, and menisci with high clarity, and has over 90% accuracy in detecting meniscus injuries.

In addition to confirming the presence and location of a tear, MRI can also reveal:

- ACL or PCL tears

- Collateral ligament injuries

- Cartilage defects or degeneration

- Bone bruising or swelling

Because of its detailed imaging capabilities, MRI is typically recommended when:

- Clinical tests are inconclusive

- There’s a possibility of combined injuries

- Surgical planning is needed

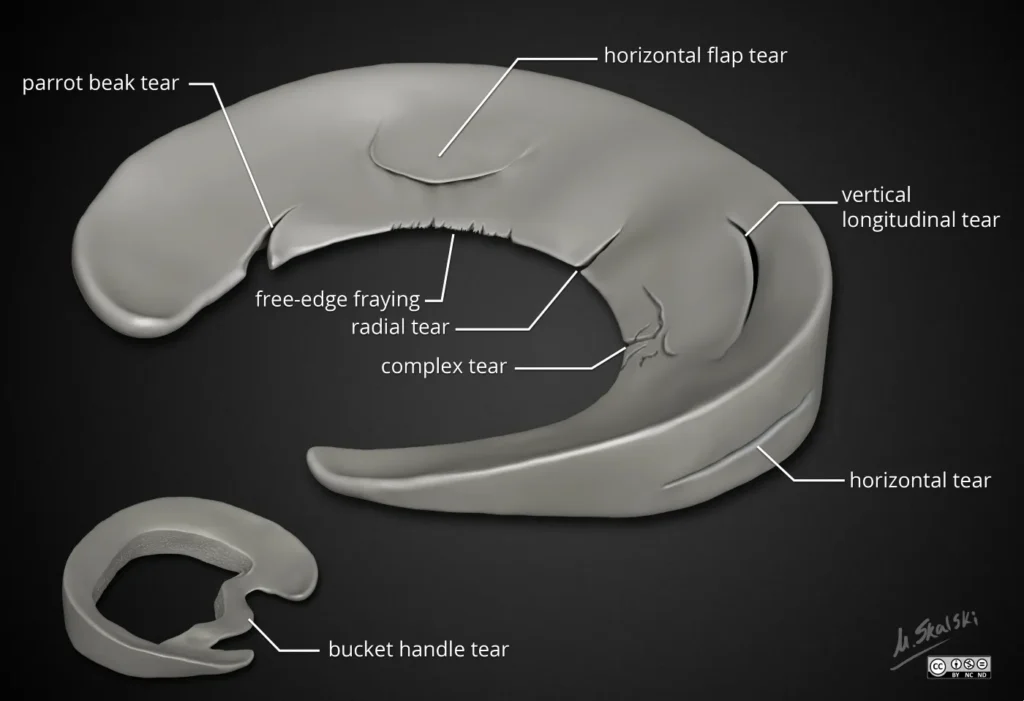

Meniscus Tears Types

Doctors classify meniscus tears based on their shape and location, which MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can clearly show. This classification helps physicians assess the potential for spontaneous healing and choose the most appropriate treatment — whether conservative management or surgical intervention.

Different tear patterns behave differently. Some are more likely to heal on their own (especially if they occur in the vascular, or “red zone”), while others are less stable and often require surgery.

Common Types of Meniscus Tears

| Tear Type | Description & Features |

|---|---|

| Longitudinal Meniscus Tear |

|

| Radial Meniscus Tear |

|

| Horizontal Tear |

|

| Complex Tear |

|

| Flap Tear (Parrot-Beak) |

|

Understanding the type of tear is crucial, as some patterns—like radial or complex tears—are less likely to heal on their own, while others, particularly peripheral longitudinal tears, may respond well to conservative care.

Meniscus Injury Treatment

The treatment of a meniscus tear depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, symptoms, activity level, and most importantly, the type, size, and location of the tear.

There are two main approaches to treatment:

- Conservative (non-surgical) treatment

- Surgical treatment

Because the meniscus plays a crucial role in knee stability, shock absorption, and joint protection, preserving as much of the meniscus as possible is always the priority.

Losing significant portions of meniscal tissue can increase the risk of developing early osteoarthritis and reduced joint function over time.

Non-Surgical Treatment of Meniscus Tears

Most people with a meniscus tear do not need surgery. In the early phase, especially after an acute injury with swelling and pain — the first step is rest, elevation, and applying ice packs to reduce inflammation. Pain relievers like ibuprofen can also help ease discomfort and swelling.

In some cases, wearing a knee brace or support sleeve can reduce stress on the joint, control swelling, and make walking easier.

Physical Therapy Treatment for Meniscus Tear

Physical therapy plays a central role in recovery and is often the first-line treatment — particularly for degenerative tears or smaller traumatic injuries.

Initial rehab focuses on gentle range-of-motion exercises that do not cause pain. Over time, these are gradually replaced by strengthening exercises, especially targeting the quadriceps muscles.

Low-impact activities like swimming and cycling are ideal, as they help maintain cardiovascular fitness without overloading the joint.

In addition to exercise-based rehabilitation, several supportive therapies can help manage pain, accelerate recovery, and improve overall knee function.

- Muscle stimulation (EMS) helps rebuild strength, particularly in the quadriceps.

- TENS and interferential currents may reduce pain.

- Laser therapy and magnetotherapy are sometimes used to promote tissue healing and reduce discomfort.

For degenerative or small traumatic tears, physical therapy is usually recommended over a period of 4 to 6 weeks. Many small tears — especially those in well-vascularized zones — can heal spontaneously with this conservative approach.

Meniscus Tear Surgery (Knee Arthroscopy)

If significant symptoms persist despite physical therapy, knee arthroscopy may be a suitable next step.

In general, arthroscopic surgery is considered in the following cases:

- A meniscus tear located in the outer “red zone” (well-vascularized area), particularly in patients under 40, where meniscus repair is possible.

- Displaced meniscal tears, where a loose fragment is causing locking or catching in the joint.

- Meniscus tears that occur together with an ACL injury.

Today, open knee surgery is rarely performed. Instead, arthroscopy is the standard surgical technique. It involves small skin incisions through which a camera (arthroscope) and fine instruments are inserted into the joint to examine and treat internal damage.

What Can Be Done During Knee Arthroscopy?

Depending on the type and extent of the tear, the surgeon may perform:

- Partial meniscectomy – removal of the damaged part of the meniscus

- Meniscus repair – suturing the torn tissue to preserve the meniscus

- Meniscus transplant – replacing the entire meniscus with donor tissue

Meniscectomy or Partial Meniscectomy

This is the most common procedure. Only the damaged portion of the meniscus is removed, preserving as much healthy tissue as possible.

Most patients can bear weight on the leg immediately after surgery, and full range of motion is usually restored within a few weeks.

Total meniscectomy (removal of the entire meniscus) is rarely done today due to long-term consequences.

Meniscus Repair

In certain cases, the meniscus can be sutured together, especially if the tear is in the outer red zone where blood flow supports healing.

Meniscus repair helps preserve joint health, but it requires a longer recovery period than meniscectomy because the tissue needs time to heal.

Meniscus Transplant

When a large portion of the meniscus has been removed and the patient continues to experience pain or functional limitations, meniscus transplantation may be considered.

This involves replacing the damaged meniscus with donor tissue of the same size and shape. It’s most commonly offered to younger, active individuals seeking to avoid joint replacement surgery.

Preserving the Meniscus Is Key.

Whenever possible, the goal should be to preserve or repair the meniscus — not remove it.

Removing too much meniscal tissue can accelerate cartilage wear and lead to early-onset osteoarthritis of the knee.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Meniscus Tears

1. Can a Torn Meniscus Heal on its Own?

The inner part of the meniscus (the “white zone”) has poor blood supply and cannot heal on its own. However, tears in the outer vascular zone (the “red zone”) may heal spontaneously with proper conservative treatment. Full healing depends on the location, size, and type of the tear. Read more in detail in separate article!

2. Do I Need Surgery Right Away?

No.

Surgery is not always necessary. In most cases, doctors will first recommend non-surgical treatments such as physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and activity modification. Surgery is usually considered only for severe tears with persistent pain, mechanical locking, or when conservative treatment fails.

3. How Long Is Recovery Without Surgery?

For mild meniscus tears, recovery may take 4 to 6 weeks with guided physical therapy.

In more complex cases, it may take up to 3 months, and if symptoms persist, arthroscopic surgery might be needed.

4. How Long Is Meniscus Surgery Recovery Time?

After arthroscopic meniscus surgery, most patients return to normal daily activities within 4 to 6 weeks. However, full recovery, especially for those returning to sports, typically takes 3 to 6 months — depending on the procedure performed and extent of the damage. Physical therapy is essential to rebuild strength, improve range of motion, and prevent reinjury.

5. How Much Rest Is Needed After Meniscus Surgery?

- After a partial meniscectomy, most people need 1 to 2 weeks of reduced activity with gradual return to weight-bearing.

- After a meniscus repair (suturing the tissue), the recovery is longer — usually 4 to 6 weeks of limited weight-bearing to allow the sutures to heal properly.

In both cases, following your surgeon’s and physiotherapist’s instructions is key to safe and effective recovery.

Makris EA, Hadidi P, Athanasiou KA. The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011 Oct;32(30):7411-31. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.037. Epub 2011 Jul 18. PMID: 21764438; PMCID: PMC3161498.

Raj MA, Bubnis MA. Knee Meniscal Tears. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

Bhan K. Meniscal Tears: Current Understanding, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus. 2020 Jun 13;12(6):e8590. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8590. PMID: 32676231; PMCID: PMC7359983.

Anderson AF, Irrgang JJ, Dunn W, Beaufils P, Cohen M, Cole BJ, Coolican M, Ferretti M, Glenn RE Jr, Johnson R, Neyret P, Ochi M, Panarella L, Siebold R, Spindler KP, Ait Si Selmi T, Verdonk P, Verdonk R, Yasuda K, Kowalchuk DA. Interobserver reliability of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med. 2011 May;39(5):926-32. doi: 10.1177/0363546511400533. Epub 2011 Mar 16. PMID: 21411745.

Luvsannyam E, Jain MS, Leitao AR, Maikawa N, Leitao AE. Meniscus Tear: Pathology, Incidence, and Management. Cureus. 2022 May 18;14(5):e25121. doi: 10.7759/cureus.25121. PMID: 35733484; PMCID: PMC9205760.

Doral MN, Bilge O, Huri G, Turhan E, Verdonk R. Modern treatment of meniscal tears. EFORT Open Rev. 2018 May 21;3(5):260-268. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170067. PMID: 29951265; PMCID: PMC5994634.

Smoak JB, Matthews JR, Vinod AV, Kluczynski MA, Bisson LJ. An Up-to-Date Review of the Meniscus Literature: A Systematic Summary of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020 Sep 9;8(9):2325967120950306. doi: 10.1177/2325967120950306. PMID: 32953923; PMCID: PMC7485005.

Mameri ES, Dasari SP, Fortier LM, Verdejo FG, Gursoy S, Yanke AB, Chahla J. Review of Meniscus Anatomy and Biomechanics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022 Oct;15(5):323-335. doi: 10.1007/s12178-022-09768-1. Epub 2022 Aug 10. PMID: 35947336; PMCID: PMC9463428.

Hohmann E. Treatment of Degenerative Meniscus Tears. Arthroscopy. 2023 Apr;39(4):911-912. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.002. PMID: 36872031.

Howell R, Kumar NS, Patel N, Tom J. Degenerative meniscus: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment options. World J Orthop. 2014 Nov 18;5(5):597-602. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.597. PMID: 25405088; PMCID: PMC4133467.

Giuffrida A, Di Bari A, Falzone E, Iacono F, Kon E, Marcacci M, Gatti R, Di Matteo B. Conservative vs. surgical approach for degenerative meniscal injuries: a systematic review of clinical evidence. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020 Mar;24(6):2874-2885. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20651. PMID: 32271405.

Simonetta R, Russo A, Palco M, Costa GG, Mariani PP. Meniscus tears treatment: The good, the bad and the ugly-patterns classification and practical guide. World J Orthop. 2023 Apr 18;14(4):171-185. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v14.i4.171. PMID: 37155506; PMCID: PMC10122773.

Dawson LJ, Howe TE, Syme G, Chimimba LA, Roche JJW. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating meniscal tears of the knee in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 7;2017(9):CD011411. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011411.pub2. PMCID: PMC6483631.

https://fizijatar.hr/koljeno/lijecenje-meniskusa-bez-operacije/